Presented in Tangier, Morocco on June 5, 2011 at ICPS annual international conference “Intermediality and Theatre”

Writing from London on one of its greyer and definitely less swinging days, I have to envy your being in bright, colorful Tangier. There you are, scanning intersections between theater and new media near the geopolitically crucial meeting-point of the Mediterranean and the Atlantic and of two continents — in a city known the world over for the lively diversity of its cultural traditions and for the drama of its topography and architecture. And Tangier is now becoming an international center of high-tech development. What better place to consider how crossings of the arts and advanced technologies can creatively mobilize a growing global awareness that, now more than ever, each of us lives on multiple planes of reality which are continually shifting and interacting.

I have asked my colleague Mitchell Chanelis to begin even farther afield in time/space than I am today from you, and to sketch the geologically long back-story of Stories Exchange Project Morocco: our collaboration in crossing international media and deeply rooted Berber and Arab traditions of theater to stimulate social and economic development. Consider, if you would, a thoroughly wired but dramatically site-specific open-plan house that Mies van der Rohe built in the middle of Europe in 1930. A star modernist architect then based in Berlin, Mies was the son of a stone-mason at the Cathedral of Aachen, completed around the year 800: a time when Islamic jihad in the Mediterranean had forced Christian innovation north northwest under the so-called Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne.

Now a UNESCO site, Villa Tugendhat was built in close consultation with a German-speaking Jewish textile-manufacturer and his wife for their young family. The house overlooks Brno, a small city in the Czech Republic that the Germans call Brünn – a name which is said to derive from the Welsh for “hill,” but which is also related to Brunnen, the German for well, fountain, or spring.

Fifteen years of accelerating war and holocaust would intervene between 1930, when the Tugendhats moved into their remarkable house, and April 1945, when the United Nations began challenging imperial projects at its founding at the War Memorial Opera House in San Francisco. And those meetings on the east cost of the optimistically named Pacific Ocean began two weeks after the sudden death of the principal architect of the new world body. Half-paralyzed himself, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a man passionately, compassionately committed to recycling inter-imperial war into global development projects mobilized by technological progress but rooted in mutual respect for cultural differences. And FDR had died at Warm Springs, Georgia, in what he liked to call the Little White House – under the care of a Navy cardiologist named Howard Brünn, and in a place dedicated to recovery from crippling attack which also activated implications of the name of the house on the Hudson River above New York City in which the President had been born: Springwood.

This modest structure on a small hill overlooked the polio rehabilitation center focused on hydrotherapy for which Roosevelt had served as consulting architect after a polio attack in 1921 turned his own athletic legs as if to stone. But the little house in Warm Springs was only the first and the last in a series of alternative White Houses – Casas Blancas – from which the disabled President would lead geo-political body-re-building exercises. The second would be in Casablanca itself, on a hill that overlooks the Atlantic.

But on the morning of September 12, 2001, immediately after the aborted attack on the Washington White House and the catastrophically successful assault on New York that ignited another global war from which the world is far from recovering, I found myself in the Tugendhats’ white hill-house. And looking out at a springing fountain of a willow, I was surprised to find the view – well, rehabilitating.

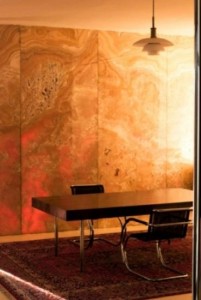

Perhaps that was no wonder. The Aachen stone-mason’s son had animated his shrine to high-tech modernism by moving delicate slabs of radiant, wave-patterned onyx north to Brünn across the Mediterranean from the Atlas Mountains—not far from where you are now. And in the context of your discussions about experiments in cross-fertilizing physical performance and tele-media, you might want to imagine this shining displaced stone as a screen. You can see it mapping the streaming subterranean fires which produced it millennia ago. But you can also see it as an atlas of variations which have been played on that long geological story by our last seven destructive – yet intermittently and potentially re-creative – decades.

Mies may have moved the stone from the Atlas Mountains to mirror the wave-springing expanses of Cipollino “landscape” marble from the Swiss Alps with which his father had helped stage the 1902 visit of the last Habsburg Empress to Aachen, the Cathedral that Charlemagne had built eleven hundred years earlier to challenge Islamic conquest around the Mediterranean. But in 1930 the light-streaming Brünn onyx also reflected and further refracted shimmering light-waves that were continually regenerated by the willow which towered over the Tugendhats’ casa blanca – until 1944, when half the great tree was burned to ashes by one of the bombers that London and Washington sent to stop the global holocaust started by Hitler and further fueled by Hirohito, Emperor of Japan.

Yet the weeping willow had sprung up to an impressive portion of its former height by the morning after Osama bin Laden turned American passenger planes into missiles and reduced to dust three thousand daughters and sons and mothers and fathers from around the world. And I was walking through the white house in Brünn on September 12, 2001 in order to continue projecting re-growth from tragedies that continue to proliferate around the globe. I was there because Mitchell Chanelis and I had heard that Grete and Fritz Tugendhat used their house to stage and film theatrical improvisations in order to raise money with which to re-house fellow Jews whom Hitler had forced out of their homes in Germany and Austria— until 1938, when the Tugendhats themselves abandoned their extraordinary house so as not to join members of their families in Theresienstadt, an eighteenth-century Habsburg fortress town that Hitler would use as a holding-pen for Jews en route to the barracks, gas chambers, and crematoria of Auschwitz-Birkenau. With broadcast footage of the falling towers running in feedback loop through my head, I was talking with a curator from the Brno City Museum about how passionate Sunday photographer and film-maker Fritz Tugendhat had convinced Mies van der Rohe to incorporate in his domestic updating of imperial Aachen a dark room, film projection booth, and a giant roll-up screen. The house seemed to be an ideal site for further development of an experiment in focusing international attention on the creativity of marginalized peoples that Mitch and I had staged and shot just a year earlier in around the imperial architecture of Theresienstadt.

Since 1995 we had been working closely with Czech Roma. They are people whose ancestors had come from India around the time that Emperor Charlemagne was building Aachen Cathedral, but who owe their name in English, “Gypsies,” to the mistaken notion that they came from Egypt. For centuries the Roma had wandered the roads of imperial Europe, served its armies, and died along with millions of Jews and others in Hitler’s work and extermination camps. And like the Jews, the Roma had learned to build rehabilitating virtual homes for their springing spirits in music and stories which still show no sign of running out. Mitch and I had worked with Roma leaders and their families to mobilize story-theater, video, and Web-sites in order to help build rooted new homes for fellow-Roma which would be at least as well equipped with imagination, if not electrical devices, as the Tugendhats’ high-tech show-house. And in September 2000, along with our cameras we brought to the Attic Theater of Theresienstadt Jewish and Roma Holocaust survivors and their families; President Václav Havel’s human rights team and other dissidents who had helped make the Velvet Revolution; the serving U.S. Ambassador to Prague who had been President Clinton’s Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights and Democracy; Roma musicians from around the Czech Republic – and members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

But we were ultimately blocked from using the Tugendhats’ white house to build further on our intermedial experiments in Theresienstadt by the second Bush Administration’s very different responses to the Bin Laden attacks of the following September. When I first spoke with art historian Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat in Vienna at the beginning of 2002, she was thrilled by the idea of opening her family’s house to our Roma friends and colleagues. Not long after our conversation began, she sprang up and led me downstairs to meet a young Roma cellist to whom she was renting a room, and insisted that we start right away working with him. But when the so-called War on Terror escalated and deviated to Iraq, Daniela phoned me in Cambridge, Massachusetts to bow out: “What has happened to your country, Jack? And who are you really working for?” I assured her that Americans were far from united in supporting George W. Bush’s diversionary military projections of democracy on Iraq, which seemed to have had nothing to do with the attacks on New York and Washington. But the trust was broken. And this was only the beginning of a gathering of suspicion among European colleagues which brought down the curtain on what we had already begun to call the Tugendhat Project.

Eleven years later, with a strikingly different President now in Washington and after the discovery and death of bin Laden in Pakistan, we are working with diverse Moroccan and international partners to build productive variations on our Theresienstadt work—indeed at, and around, a white house on a hill. But now the house is in its namesake city, and much nearer the Atlas Mountain source of Tugendhats’ springing, mapping onyx.

Dar es Saada in the Anfa section of Casablanca is one of several attempts in the 1930s by architects based in the capitals of the European empires—themselves already mortally fractured as well as mechanized by a first global war – to translate modernism south southwest across the Mediterranean to the origins of the Islamic challenge Aachen was built to counter eleven centuries earlier. Certainly the Swiss architect of Dar es Saada, Erwin Hinnen, was both far less deeply rooted and far less innovative than Mies of Aachen, who translated north a symbolic fragment of a North African moutain range to drive projections around the world of images of his solo modernization and calculated fragmentation of the imperial vision of his childhood home in a lavish house that he built for a single family on a willow-springing hill in Brünn. But when the passionately and compassionately anti-imperial founder and co-architect of Warm Springs made Dar es Saada his first trans-Atlantic White House by playing world-changing multi-media variations on Hinnen’s effort to integrate European and Moroccan building practices, the Casablanca villa became an even stronger contender for world attention than Villa Tugendhat. And we believe that it can now once more assume responsibilities which go with such prominence: now that the Arab Spring’s indigenous if Facebook-facilitated projections of democracy have made North Africa again an arena for re-cycling worldwide war into equally strenuous waging of peace – both on the World Wide Web and in person, not only in the different port-cities where you and I are today, and in as many other places in the world that we, and visitors to stories-exchange.org, can project.

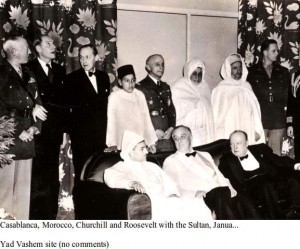

In January 1943 at the Casablanca Conference, Franklin Roosevelt turned to globally productive use the Swiss architect’s effort to marry Moroccan traditions and European modernism. At Dar es Saada on January 22, against a backdrop of floral and swan-graced waves of a curtain which translated indoors the garden it concealed and gave it an appropriately hydrotherapeutic accent, FDR of Warm Springs assembled other Moroccan, French, British, and American guests for a series of informal photos with his own guest of honor. Sultan Mohammed ben Youssef, the future Mohammed V, had already distinguished himself by protecting Moroccan Jews from the Hitler-propitiating Vichy government of France. And during dinner, the President and the future King had conversed about how they could cooperate after the war in developing irrigation projects that would enable Moroccan farmers to feed their families and fellow-citizens.

Thirty years later the Sultan’s son and successor as King Hassan II would write: “It was after the Anfa interview, and as a result of the promises that were made there to him, that my father led the Moroccan people resolutely on the road to independence…. I was 14 years old and, as can be imagined, in such illustrious company I was all eyes and ears… The President said he thought the colonial system was out of date and doomed. …He foresaw the time after the war – which he hoped was not far off—when Morocco would freely gain her independence, according to the principles of the Atlantic Charter. After the war, he said, the politico-economic situation of human society must be reorganized. The United States would not put any obstacle in the way of Moroccan independence; on the contrary, they would help us with economic aid.”

Writing only three years after the dinner, though, Roosevelt’s son Elliott would describe the exchange in greater detail, and characterizing it rather as a mapping of positive, interactive cooperation: a post-imperial experiment in two-way interdependence: “Father and the Sultan were animatedly chatting about the wealth of natural resources in French Morocco, and the rich possibilities for their development. …The Sultan expressed a keen desire to obtain the greatest possible aid in securing for his land modern educational and health standards. Father pointed out that, to accomplish this, the Sultan should not permit outside interests to obtain concessions which would drain off the country’s resources….The Sultan sadly shook his head as he deplored the lack of trained scientists and engineers among his countrymen, technicians who would be able to develop such fields unaided… Father suggested mildly that Moroccan engineers and scientists could of course be educated and retrained under some sort of reciprocal educational program with, for instance, some of our leading universities in the United States… He mentioned that it might easily be practicable for the Sultan to engage firms – American firms – to carry out the development program he had in mind, on a fee or percentage basis. Such an arrangement, he urged, would have the advantage of enabling the sovereign government of French Morocco to retain considerable control over its own resources, obtain the major part of any incomes flowing from such resources, and indeed, eventually take them over completely.”

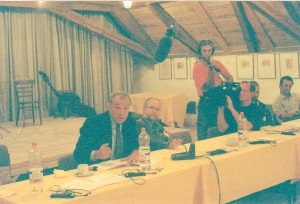

projection: FDR, Churchill with press on lawn

And only two days after the dinner, the President himself offered the first of two emphatic characterizations of the reciprocity of the trans-Atlantic cooperation in agricultural hydrotherapy that the Sultan and he had discussed at table, also providing a model for the architecture-driven inter-medial theater that Stories Exchange Project Morocco will be using to energize contemporary variations on the substitution of exchange for imperial remote control that FDR and the future Mohammed V projected. On the other side of the photo-curtain’s lavishly flowing blossoms, on January 24th Roosevelt turned the garden into a high-tech but small and quiet version of performances in the Djem el Fna, the great square of Marrakech in view of the Atlas Mountains. FDR’s special assistant and close friend Harry Hopkins would record in his journal that evening: “We drove to Marrakesh.. .Averell, Randolph, Robert and I went to visit a big fair—story tellers—dancers—snake charmers. Very colorful.” Hopkins’ breezy shorthand refers to the vigorously physical, often acrobatic building of improvised story-circles that Moroccans call halqa, “link” in Arabic. This vibrant indigenous form of theater may be emphatically low-tech, but it lives up to its name by networking at least as ambitiously as our electronic interactive media. Halqa invites anyone who comes along – men and women of any social class, race, or nationality – to join in opening perspectives potentially as new as those which FDR generated when he translated his face-to-face exchange with the Sultan for the global media.

At noon on January 24th the President had used the garden façade and pergola of Hinnen’s modernist casa blanca as a visually stimulating backdrop for a more expansive conversation with dozens of photographers, camera-men, and print and radio journalists who had been secretly flown in for the occasion. Astonished to see the American Commander-in-Chief in North Africa only six weeks after the Allied invasion had begun to drive out the Germans, they were seated in a halqa-like semi-circle on the grass at the Allied leaders’ so differently capable feet—poised to spring up and flash around a globe at war their host’s realistically pacific because collaborative improvisations. He talked about “the common objective that brings us to these parts—to improve the conditions of living in these parts, which you know better than I do have been seriously hurt by the fact that during the last two years so much of the output, especially the food output of French North Africa, has been sent to the support of the German Army. That time is ended, and we are going to do all we can for the population of these parts, to keep them going until they can bring in their own harvests during this coming summer. Also, I had one very delightful party. I gave a dinner party for the Sultan of Morocco (Sidi Mohammed) and his son. We got on extremely well. He is greatly interested in the welfare of his people.”

And then, just eleven months later, on October 19 Roosevelt was able to tell journalists in Washington, “Agricultural experts sent over a lot of seeds and things like that, in order to expand local agricultural production…Some of the shipments began to get over there way back in early spring, and arrived in time for the harvest in June and July. The remainder …especially the seeds, will arrive in time for fall planting this year, for harvest next year… Food imports into North Africa have stopped entirely since the first of July. In other words, they are self-sustaining….In the coming year 1944, these harvests in North Africa, aided by mounting agricultural help and a year of peaceful cultivation, should greatly ease the strain on the United States:…We won’t have to ship as many food products out of the United States as we would have otherwise. It works both ways.”

It can work both ways, and if it doesn’t, it’s not worth trying: this is the architect’s square that Mitch Chanelis and I have been using in all our work. In Morocco we are building a team of local men and women in the electronic and print media, in theaters, and in universities and schools, along with an emerging coalition of managers of businesses both large and small, international and Moroccan. We and our several partners aim to enable younger Moroccan men and women from economically disadvantaged communities to develop and demonstrate to their nation and the world employable skills in communication and management, both cyber-mediated and in real time and real space. And now we are working against the clock to go public with Stories Exchange Project Morocco by January 2013, in time for the seventieth anniversary of the pivotal encounter between FDR and the future Mohammed V.

Well before that we will be further developing our collaboration with African-American writer and director Robbie McCauley. Robbie’s 1992 Sally’s Rape, about her great-grandmother, a slave, won an OBIE award for best off-Broadway play in New York, and in 1995 she became Artistic Director of the first round of Stories Exchange Project Prague. In May 2012 Robbie will lead workshops in Tangier, Tetouán, Rabat, and Casablanca. She will begin training young Moroccans, their parents, and grandparents to work together in recording stories about efforts that they and their friends and neighbors have made to overcome difficulties; to tell the stories with maximum intensity and effect—as Robbie says, “with energy, joy, beauty, power”; to perform and talk about the stories with audiences throughout the country; and to work with our media partners in translating these performances and discussions for global dissemination by video and interactive Internet presentation.

With Robbie and a rainbow of Moroccan partners in Tangier, Tetouán, Rabat, and Casablanca we will also be playing further variations on another translation of halqa that helped us move the Stories Exchange Project to Theresienstadt

In August 2000 our Roma friend and colleague Eva Bajgerová and her team put up a little casa blanca across from the City Hall in the main square of a small city near the Czech-German border that the Germans call Aussig and the Czechs Ustí nad Labem. The art that came out of Eva’s little tent was as low-tech as you can get, but it spoke directly to realities on the ground in a town where Czechs had not long before put up a wall between themselves and their Roma neighbors – and kept it up until international protest forced the city to take it down.

In the Scientific Library across the square in Aussig we had set up computers for kids and their parents and grand-parents to use in reading and writing stories for the Stories Exchange Project.

But in the tent itself little Roma were simply using rainbow upon rainbow of colored pencils and crayons to design their own houses, putting the drawings up all over the outside walls of their new little traveling home, and inviting people who were crossing the square to register to vote and pay their taxes and so forth at City Hall to stop by and talk over coffee about how Czechs and Roms might get together to build more useful things than walls, even more lasting houses.

But how can we best translate what was going on in this little mock Tugendhat house, in our computer installation in the Aussig library, and in the theater and music, the discussions, and the video-making in Theresienstadt? How can we most effectively translate all this low-to-high-tech stories exchange from the middle of Europe to the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts of Morocco by the seventieth anniversary of the 1943 conversation between the founder of the United Nations and the future king of a free Morocco? We welcome your suggestions and help in making Dar es Saada once again what it was seven decades ago: a wired and lively stage from which to project around the globe productive— seeding, feeding, and springing – updatings of halqa.

Recent Comments